The mountain pour

January 25th, 2014, 12pm in Kamakura, Japan

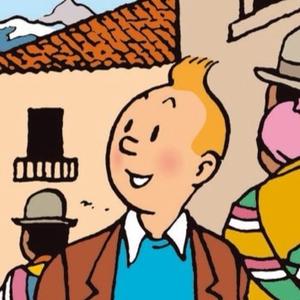

Let's just say Fingerface Palmieri wasn't leaving this mountain without making coffee.

He had a crazed look in his eyes. Said he had "carried" fire all the way up the mountain and, good lord, he wasn't going to "carry" it down, too. Said some sweet angel called Eiko taught him how to do this, and how this had become a life-defining act: diving a dark, rich nectar high above ancient Kamakura. Like old men do, you know, right? he added, cryptically, before climbing higher still.

Our group was small but potent. Anything could happen. Fingerface, An Amal, and I. An Amal had his first taste of tofu the night previous and I think his life was changing before our very eyes.

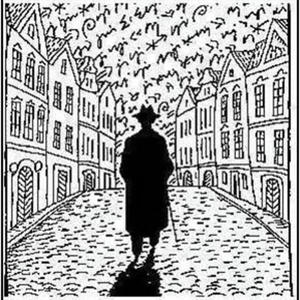

The plan was simple: disembark the Shonan Shinjuku Line at Kita-Kamakura Station, nearby the grave of master filmmaker Yasujiro Ozu and climb. Climb over a mountain to the towering bronze Buddha — cast in 1252 — crouch inside the creature and slap its belly from within, an act symbolic, if somewhat overly dramatic. Something to ground us in time and place before we thrust ourselves into the virtual of the coming week.

As we stepped from the train, I noted the long untouched, unblemished Kita-Kamakura station of the Ozu films — the staid platform, the open roof that you often see in his train shots — was done. To be seen never again. Not in "real" life anyway. It has been scaffolded over, in the process of "reform," to be made more "palatable" by modern standards. Sayonara, Ozu's station. Who knew the portentous nature of this desecration.

The roots of the trees grew over our path in endless, complicated, tight patterns. It looked like the folds of a brain if you peeled back a skull. I began to wonder whose cursed skull, exactly, it was atop which we traversed. Atop which we sweated. The weather unseasonably warm. Cruel, you might say. Fingerface was down to his final layer, threatening to strip even further if Mother Nature didn't "cut us a bitta slack." An Amal looked concerned. I whispered to him, just don't make eye contact.

Hours passed. It was clear we were close to the end of the mountain trail. The soft swoosh of cars could be heard nearby, below. We had searched and failed to find a spot for Fingerface to decant his "medicine." He grew increasingly indignant: We gotta find the spot, gotta.

Good god, how badly did this man need his coffee? And did we really have to do it on the mountain?

At the very last moment I noticed a side trail, one of which I knew few hikers used. Here, I implored, let's try here, all the while hoping Fingerface wouldn't do anything rash or manic. How does one, precisely, assuage the devil?

We climbed and there was a man with a dog and a child. We said hello and they mercifully left. We were alone. This was the spot.

The bracken was voluminous. We swept as best we could. An Amal procured a slab of granite. Fingerface went to work, a man possessed. I never saw the world recoil from someone as I did in that moment, Fingerface bent over his tool kit, eyes on the Colombian bean prize.

The gas canister hissed like a punctured bike wheel just before the flames exploded. They missed a dry patch of leaves by millimeters. Wait, shouldn't — QUIET YOUR TRAP! screamed Fingerface, arm flailing behind him. I'M WORKING.

The water boiled. The beans were ground. The conflagration stayed near the canister, the forest survived. Fingerface questioned the amount of beans I had ground but in the end the coffee was good, if a little thin. It nourished us all. An Amal flopped to the forest floor in relief. The demons of Fingerface were satiated.

On the train back, exhausted, Fingerface slept. An Amal turned to me and whispered: Is this how all the Hi offsites go? And I said, Yes. Yes, every single one, An Amal. Every single one.

Nobody died. This was going to be a good week.